Happy almost-April, everyone. March is one of those months where my goal is pretty much to SURVIVE. I’m happy to report that I’m still standing, as of 2:45pm on March 29th. [edit: It’s now March 31st. Still standing]

Earlier this month I had a great professional opportunity — along with my good friend Angie, we were invited to participate in UBC’s Speaker Series on Teaching & Learning in Science through the Lens of Indigeneity, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion.

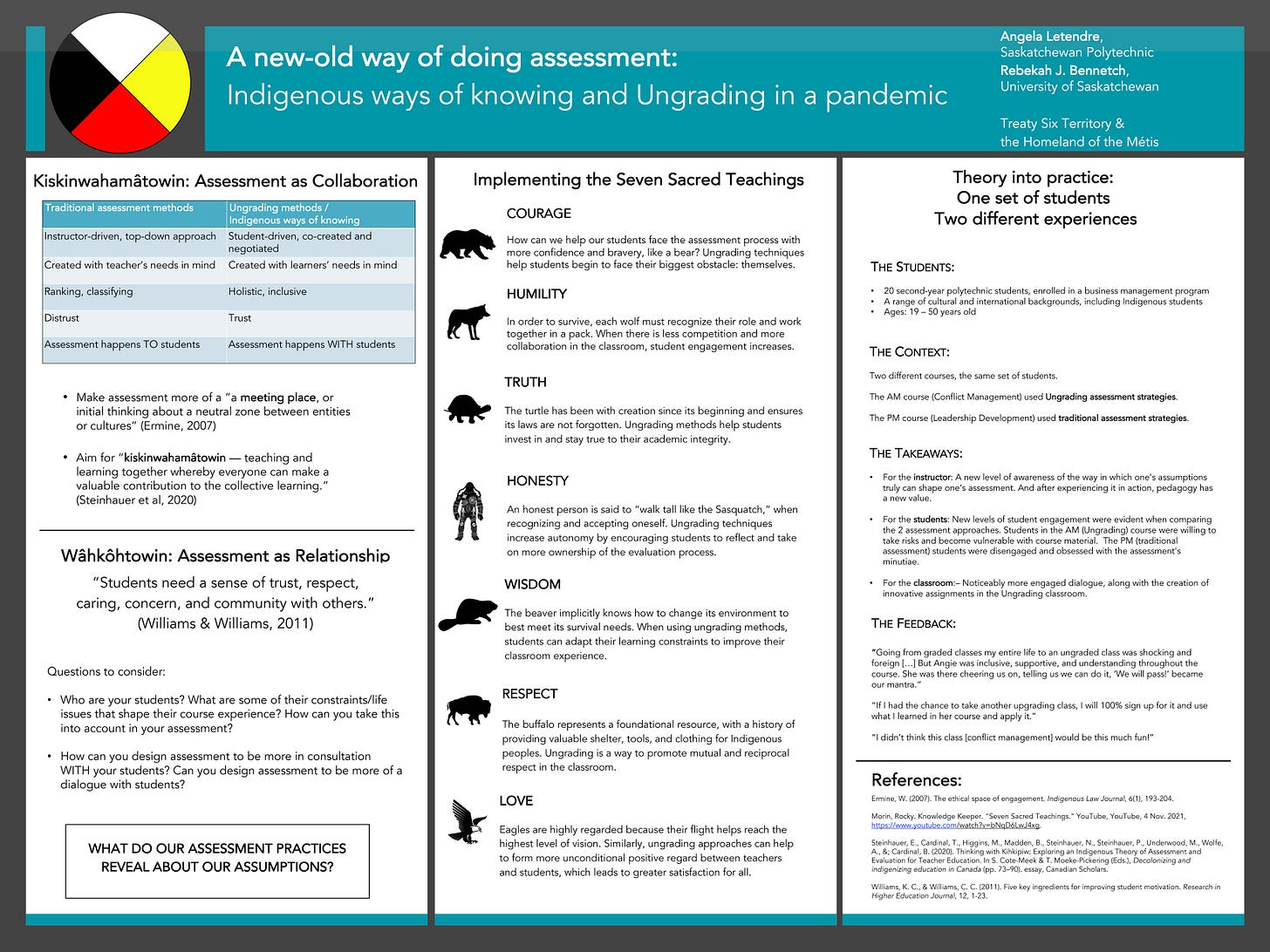

Our talk expanded upon the work we began at last year’s STLHE conference, where we started exploring alternative assessment strategies and how this “new” pedagogical practice actually has its roots in much the more traditional (or “old”) Indigenous Ways of Knowing. Much of our UBC talk was about how we have since continued to find ways that align our current assessment practices with the values of these traditional ways.

For me, a white settler, I have always struggled with finding meaningful ways to show my respect for the Indigenous and Métis peoples who have come before me. I do have a personalized land acknowledgement that I give before any major event, but I know there are many more active ways I can show my support and appreciation.

Last year when Angie and I first saw the overlap of ungrading techniques with Indigenous values and practices, I knew this was one pedagogical avenue that could work for me and my assessment practice. It’s been such a fulfilling journey to learn about the Cree and Anishinaabe peoples and how their wisdom can help shape my choices in the classroom.

As part of my talk this month, I quoted Thomas King, and asked about what an act of “kinship” could look like in assessment:

I’ve written about this before, but as I lean into my perimenopausal ways, more than ever I want to embrace the teacher identity of who I want to be — and not force myself into the norms and “rigour” of other academic boxes or identities. Part of the leaning-into my identity is to choose to work from a more collaborative POV, which links back to the idea of kinship.

I no longer want students to feel like assessment is something that happens TO them — I want them to feel included in the process, so that it’s more of a happening WITH. To do that means I need to find the ways to be more harmonious with the students in my classes, and each day I try. (most days, I succeed)

The Cree word for this kind of intentional practice is Kiskinwahamâtowin — a mutual process where we learn from each other. The old ‘sage on the stage’ isn’t for me. I am much more comfortable (and happy!) when I can be more of a coach or mentor. Because, ultimately, it’s not up to me to teach students — but I can give them the materials and tools for them to help teach themselves.

Another way that Indigenous Ways of Knowing have shaped my practice has been in understanding the “warm demander” approach to teaching. This originally came from understanding the educational journey of many Indigenous students from Alaska. In the mid-1970s, a researcher noticed that the more effective classroom approaches were the ones that balanced both compassion + accountability in their approaches.

When teachers skewed too much to the “compassion” angle — they were too patronizing and students disengaged. Those teachers who went too far over to the “accountability” side didn’t have the relational connections to help their students invest. It was the magical balance of emotional warmth + active demandingness that made a difference in these students’ lives.

I didn’t realize it, but that’s my pedagogy in a nutshell. I love to connect to my students on personal levels, and (not but!) I still have high expectations for them to rise to the occasion.

On the first day of classes this term, I had a moment where this became strikingly clear. I always like to ask students what they have heard about the course — it’s a required course in two technical colleges, and most students are not very happy or keen to be forced to take it. One of my students’ answers this year wasn’t about what they had heard about the course — it was what they had heard about me, the instructor:

I hear you’re the hardest marker in the department.

I have massive respect for the student to be brave enough to say that to someone they’ve just met. And, it set me up for the perfect “teaching moment” to let students know that yes, yes I do have high expectations for them. But I also got a chance to talk about how I’m here to help them. I know they can do it, and I’ve got their back.

Since I’ve started embracing this approach, it’s changed everything. And I can say, for the first time in my career, that I’ve had students actually THANK me for failing them on an assignment. I work on implementing more of a growth-mindset in my assessment, and students know they can have another shot at re-doing their work. And if they choose not to try again, that’s okay too.

Now that I think of it, it’s quite something to be able to write positively about assessment at the end of Term 2, considering the avalanche of grading in the days before me.

I’m grateful I can stop and reflect and learn from those who came before me, especially on this land that I call home.

Things that have brought me joy over the last little while:

I’ve been invited to be a guest editor for our campus’s undergraduate research journal, and this issue looks like the perfect Rebekah topic: “Disrupting and Expanding the Status Quo”

I’m nearly done my dissertation proposal (I think?). It’s been quite the journey to look at some difficult parts of my educational journey as I start to process my “narrative beginnings.” I’m hoping to have it defended by the end of May.

There’s 2 conferences in my future May-June, one online and the other in Charlottetown, PEI. Send me all your reccs now (and yes, Green Gables is on the list)

Twitter is still dying, but there’s some bright spots like Pedro Pascal as mushrooms and Canadian PMs as lead singers of heavy metal bands

My students are all almost finished giving their 5-min persuasive speeches, and I’m so proud of them. This is the best part of the term, where we are a true learning community.

Mainly, I’m just trying to survive until the end of term. I think I’ll make it.